As a general rule, a portfolio of loans to borrowers of prime credit standing would experience a lower level of defaults and bad debts than would a portfolio of loans to borrowers of sub-prime credit standing. This, however, does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that an investment in a portfolio of loans to borrowers of prime credit standing has a lower risk than investing in a portfolio of loans to borrowers of sub-prime credit standing. That is because the loans to borrowers of prime credit standing are priced at a much lower level than are loans to borrowers of sub-prime credit standing.

In an efficient market (which by the way we do not have in Australia) incremental increases in risk would be matched by incremental increases in pricing. The reality, however, is that a borrower that does not fall within the ambit of prime credit standing is required to pay a significantly higher price than does a borrower of prime credit standing. The increase in price is much larger than the increase in risk. As a result, a portfolio of sub-prime loans could have a higher return-for-risk than would a portfolio of loans of prime credit quality.

For example: A portfolio of conservatively geared home loans to high credit standing borrowers might be earning a return of 5% pa (before bad debts) but incurring a bad debt write-off of 0.5% per annum, leaving the portfolio with a net return of 4.5% per annum. On the other hand a portfolio of small ticket unsecured loans to borrowers of sub-prime credit standing might be earning a return of 30% pa but incurring a bad debt write-off of 10% per annum, leaving a net return of 20% pa. In this example the portfolio of sub-prime unsecured loans would offer a higher return-for-risk than would an investment in the portfolio of loans to borrowers of prime credit standing. An investment in the sub-prime portfolio would therefore be preferred over the one of prime credit quality.

Portfolios of loans to borrowers of prime credit standing are often leveraged, resulting in the investors having a reasonable expectation of earning a return that is higher than the return that the portfolio is generating.

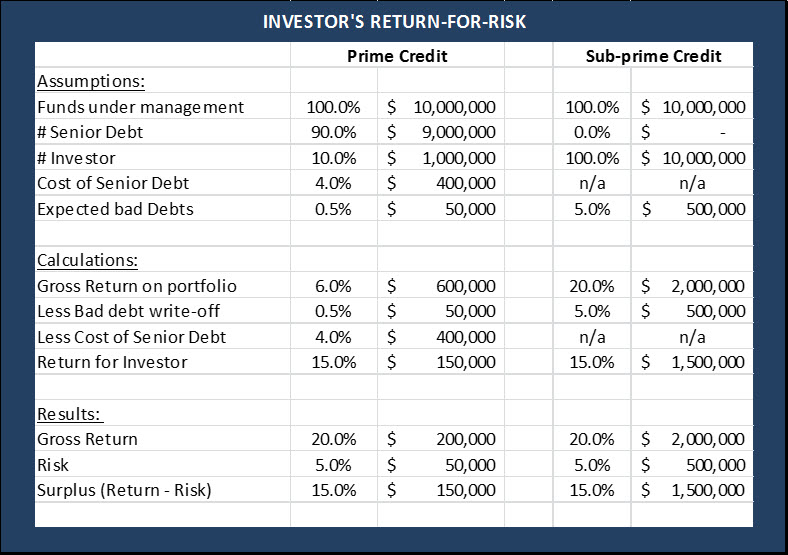

The question then is how to compare such an investment (in a subordinated piece of a leveraged loan portfolio to borrowers of prime credit standing) to an investment in a loan portfolio to borrowers of sub-prime credit quality. The approach I would take is set out in the table below:

Since the gross return, bad debt risk and net return for the investors in the table above are the same for the prime portfolio as they are for the sub-prime portfolio, it would appear that the investments would have equal merit. This is however not the case. An investment in the sub-prime portfolio would be preferred because in the case of the prime portfolio the investor ranks behind another party, the senior lender.

The senior lender’s loan agreement would give it additional rights over those granted to the investors in the subordinated piece. This could give the senior lender the right to stop any payments of interest or repayments of capital to the investors in the subordinated piece – at least until the senior lender has been repaid all amounts due to it.

In addition to this, any fees payable to an administrator or liquidator (which are often exorbitant) rank ahead of the subordinated investor’s rights. Compounding the problem for the investors in the subordinate piece is that administrators and liquidators in practice act for the party that feeds them, the senior lenders. I am not sure how to determine what additional return I would require to compensate me for bearing this disadvantage, suffice to say that the additional return I would want would be substantial.

Prepared by: Mark Morris